Doug Crusan’s place in NFL history holds strong more than 50 years later, the Miami Dolphins 1968 first-round pick still part of the league’s only perfect team.

The 1972 Dolphins, coached by Don Shula, quarterbacked by Bob Griese and led in brawny bullying by running back Larry Csonka — the “less famous” first-round pick of 1968, Crusan likes to joke — had a 17-0 final record and a 6-foot-5, 275-pound starting offensive tackle in Crusan. That was big for its day. And it makes his other championship team of legend, the one so many more people have been talking about in the past few months, even more of a curiosity.

The 1967 Indiana Hoosiers won one of two Big Ten football championships in school history, still the most recent, though the 2024 Indiana Hoosiers are in a 12-team tournament to win a national championship starting Friday at Notre Dame. This fall naturally brings to mind that fall, in part because successful Indiana football seasons are things to be studied, like cicada broods, and in part because the 1967 guys see a lot of their coach in the Yinzer who has fire-breathed life into the Hoosiers.

“Coach (Curt) Cignetti reminds me a lot of coach (John) Pont — the intensity, the toughness, the no-nonsense kind of thing,” said Mike Deal, a sophomore cornerback on that 1967 team. “Coach Pont just made you believe, and that’s probably where I really see it now.”

The 1967 Hoosiers had Pont, a product of Miami (Ohio), the “cradle of coaches” in the era of Woody Hayes, Bo Schembechler and Ara Parseghian. They had no preseason expectations. They produced a magical season, sneaking into a void as Michigan State’s dynasty was ending and just before Hayes’ Buckeyes won it all in 1968 and joined with Schembechler’s Wolverines to take over the 1970s. They captured a campus that was between hoops coaching legends, after Branch McCracken and before Bob Knight, a campus protesting the war in Vietnam daily.

Indiana coach John Pont shakes hands with USC’s John McKay before the Rose Bowl on Jan. 1, 1968. (Bettman Archive)

Indiana had a halfback at fullback and a quarterback at halfback, who also happened to punt, except when he decided to run the ball instead, which got him in enough trouble that Hoosiers fans came up with a chant to remind him to be smart.

“Punt, John, punt!” said Kris Foley, an IU sophomore cheerleader in 1967, repeating the in-game advice of thousands for leading rusher and All-America punter John Isenbarger. “We had so much fun that year.”

The 1967 Indiana Hoosiers also had a 275-pound senior starter and NFL prospect at offensive tackle who, a few months from the start of that draft process, suddenly became a 232-pound defensive tackle. On the advice of Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, Pont ordered most of his defenders to get lighter and faster so they could run his new, blitz-heavy 4-4 defense.

That tracked. But moving a two-year starter on offense to defense, as a much smaller version of himself? Indiana football skepticism wasn’t confined to the Big Ten “sky writers” who traveled around to every campus each offseason and picked the Hoosiers last that summer.

“Coach Pont calls me in before spring ball in ’67 and says, ‘I’m going to move you to defense,’” Crusan recalled. “OK, that’s shock No. 1. Shock No. 2 comes when he says, ‘I want you to report at 235.’ I’m supposed to lose 40 pounds? I almost asked him, ‘Have you picked my fiancée for me yet?’”

Pont didn’t recruit Crusan from Monessen, Pa., to Bloomington. That was predecessor Phil Dickens, who beat out Penn State and Pitt for Crusan, continuing a pipeline from Western Pennsylvania to Indiana. Also, Pont hadn’t exactly taken the Big Ten by storm in his two seasons with the Hoosiers — they were 3-16-1, their most recent outing a 51-6 humiliation at the hands of rival Purdue.

Skepticism, warranted. The best interests of Crusan’s football career, ignored. But he did what his coach told him to do and showed up for preseason camp at 232.

“Starved me, literally,” Crusan said. “Darn near to death.”

‘Oh (s—), is something happening here?’

And it worked. Crusan’s disruption keyed a defense that keyed a championship run, and he made the All-Big Ten second team at his one-year position. The 1967 Hoosiers, much like the 2024 Hoosiers, started winning and kept winning until they opened eyes outside and inside the program.

“I don’t think anybody thought we’d go 9-1 and win the Big Ten,” said Eric Stolberg, a sophomore receiver on that team. “But sometimes you just kind of get rolling and then it keeps going and going and going.”

The defense was flush with effective linebackers, which was part of the reason for the switch to a 4-4. Ken Kaczmarek and Jim Sniadecki both had All-Big Ten seasons. Cal Snowden had a big year off the edge.

The offense was different as well with an emphasis on speed option and “scramble blocking,” executed by All-Big Ten linemen Bob Russell and Gary Cassells. But the backfield shuffle made the run possible. Sophomore Harry Gonso beat out Isenbarger at quarterback, shifting Isenbarger to halfback, shifting senior halfback Terry Cole to fullback. That trio, plus sophomore receiver Jade Butcher, made the Hoosiers dangerous.

“Without Gonso and what he did, there’s no Rose Bowl,” Deal said. “But the defense kept us in games and allowed the offense to find a lot of late magic.”

Indiana beat Kentucky 12-10 at home to start. Then it was Kansas, at home, an 18-15 decision. It was better to win than to lose. But the Big Ten beckoned. The opener at Illinois was a moment of discovery. That’s another team that handled IU the year before, in Bloomington. Before the game, Kaczmarek rewatched a long John Wright touchdown catch from the 1966 game “about 500 times” to get fired up for the rematch.

This time, Wright had to watch Kaczmarek from behind as he took an interception all the way back for a touchdown. Hoosiers 20, Fighting Illini 7.

“That was the moment where it was like, ‘Oh (s—), is something happening here?’” Deal said.

“Are we good?” Kaczmarek said. “Actually, I think we are.”

Then came a 21-17 home win against lowly Iowa. Isenbarger, who had autonomy to take off on a punt if he saw an opening, saw one wrong and nearly gave the Hawkeyes the game. Pump the brakes, everyone.

Then came a 27-20 win at Michigan. This was Bump Elliott’s Michigan, a middling team, the extension of a middling program in the 1950s and ’60s. Still, Indiana didn’t beat Michigan much. It had happened three times since Indiana’s only Big Ten championship team to date, captained in 1945 by Deal’s father, All-America tackle Russ Deal, prevailed 13-7 in Ann Arbor.

The Hoosiers were in control until Isenbarger, incredibly, saw another one wrong from punt formation and got buried deep in Indiana territory. Pont benched him, later telling Sports Illustrated that it was “the maddest I’ve ever been in my life.” Michigan tied it. Gonso begged Pont to put Isenbarger back in the game. He did, and the sophomore put together “a hellacious drive of runs,” Kaczmarek said, ending in the winning touchdown.

Indiana went from unranked to No. 10 in the Associated Press poll. The Hoosiers celebrated their newfound status with a 42-7 romp at Arizona. This was officially a situation. Indiana’s campus was all in on the team that typically served as a pre-basketball pastime.

That campus, like most around the country, was fully embroiled in the debate over the war in Vietnam. Indiana’s team had members who would later be part of it. Senior lineman Ted Verlihay would be killed in action in Vietnam in 1970. In 1967, a lot more people were still arguing on behalf of the reasoning behind the United States’ involvement.

Also, as the Hoosiers recall, it was more conversing than screaming. Violence was absent. Protests took place daily at 20-acre Dunn Meadow on campus. Foley recalled going with a sorority sister one day and countering with a sign that read “Students for Vietnam Vets,” making the point that the young soldiers sent over had no choice and deserved respect.

“There were a lot of people on both sides, and nobody really understood what was going on,” Kaczmarek said. “We thought we were fighting communism but then you hear, ‘No, no, no, you guys have got it all wrong.’ It was back and forth but it wasn’t nasty. And then it seemed to fade a bit the more we won games.”

Sports Illustrated writer Dan Jenkins was on hand for another uncomfortably close, defense-dominated win, 14-9 over Wisconsin. “Punt, John, punt!” rained down on Isenbarger each time he dropped deep to take a snap on fourth down. Jenkins churned out a paragraph that brings 2024 Indiana football to mind, writing: “Granted, the Hoosiers have not exactly overpowered the class teams of the nation. In fact, all of the poor Wisconsins on its schedule have a combined record of 12-34-3 which, as statistics go, rates up there with Germany’s record in world wars.”

A championship run, through Spartans and Boilermakers

The SI jinx was set up nicely with a trip to East Lansing next to take on the two-time defending national champion Spartans. This was not that same team, not at all, after Duffy Daugherty saw four of his stars selected in the top eight picks of the 1967 NFL Draft. The Spartans were just 2-5. But they had destroyed Michigan and Wisconsin by a combined score of 69-7, they still had Jimmy Raye at quarterback and Bob Apisa at fullback, and they represented a giant hurdle in the Hoosiers’ minds.

“That was the prove-it game, and we wanted it so bad after they hurt so many of our guys the year before,” Kaczmarek said of a 37-19 home loss to the Spartans in 1966. “For us, it was still Michigan State.”

Crusan had spent two years trying to block Bubba Smith (the No. 1 pick in 1967) and George Webster (No. 5) — “just unbelievable players,” he said — but now he was on the other side, anchoring a defense that stymied the Spartans enough to pull out a 14-13 win. The second Big Ten championship in school history was on the table.

The next week, Crusan took his place in the middle of that defense in Minneapolis. He looked across the line at guard Dick Enderle, tackle John Williams and tight end Charlie Sanders, all destined for NFL prominence.

IU’s only trip to the Rose Bowl in program history ended with a 14-3 loss to No. 1 USC. (Bettman Archive)

The Golden Gophers destroyed the Hoosiers that day, 33-7, a 13-7 game in the third quarter getting away from the Hoosiers with a series of mistakes. An ineligible man downfield penalty took a touchdown off the board. A shanked Minnesota kickoff went uncovered and into the hands of the Gophers.

“Just like the punter dropping the ball against Ohio State,” Kaczmarek said of the way a close game at Ohio State this season got away from Cignetti’s Hoosiers. “The whole thing just got away from us.”

The outside naysayers and internal doubts were back, just in time for a season-ending visit from Purdue. That’s No. 3 Purdue, a team that beat Minnesota 41-12, a team with stars in quarterback Mike Phipps and running back Leroy Keyes. Indiana had won one of the previous 19 meetings and most were Purdue blowouts, including the 51-6 romp a year earlier.

“But I liked to tell people that we really tightened up in that game after it was 44-0 at halftime,” Crusan said.

Pont gathered his seniors for a meeting before the week of preparation began. He reminded them that a win would mean a three-way tie for the Big Ten championship, which would basically ensure Indiana’s trip to college football’s most revered destination. The Rose Bowl had a “no-repeat” rule, which is how Bob Griese and Purdue went in 1966 even though Michigan State won the Big Ten. So Purdue was out. Minnesota had been to Pasadena more recently than Indiana, so the unwritten rule dictated that Big Ten athletic directors would vote for the Hoosiers to head west.

Pont told his seniors he needed them to get the young guys believing again — and angry about what happened a week earlier and a year earlier. The Hoosiers were going to hit Keyes relentlessly. They were going to add some offensive wrinkles. They were going to win.

They did. Two just-installed trap plays sprung Cole, who had taken a back seat to Isenbarger, for huge gains, one a touchdown to put the Hoosiers up 19-7. He finished with 155 yards and was named MVP of the Old Oaken Bucket game.

“I ran as fast as I could on that play,” Stolberg said of the touchdown. “And Terry blew by me like I was standing still. I was chasing him all the way down the field, just an incredible moment.”

It came down to the defense, of course. Purdue was driving for the potential winning score when Kaczmarek slammed into Purdue fullback Perry Williams inside the 5-yard line to force a fumble. Indiana recovered. Indiana celebrated, not just a championship, not just the conclusive answer to all who doubted, but the satisfaction of rare success against a bitter rival.

“It was magical,” said E.G. White, a sophomore lineman on that team, who had a better sense of the history of the thing than most — his father, Eugene White, kicked one through the uprights in 1940 to beat Purdue with the only points of the game.

Respect, hope, futility and hope again thanks to Cignetti

The celebration got an evening boost when word came through on the radio that the Big Ten had indeed voted the Hoosiers to the Rose Bowl. It would be No. 1 USC, led by junior running back O.J. Simpson, against No. 4 Indiana. It would be Indiana’s first trip to “The Granddaddy of them All,” because the 1945 championship came a year before the Rose Bowl affiliated annually with the Big Ten.

The party didn’t slow down in Los Angeles. Deal recalls a night at a Hollywood club called The Factory, sitting near the rock band The Mamas & The Papas, then finishing Mama Cass’ full bourbon and benedictine after the band departed. The party didn’t harm the preparation, and the Hoosiers acquitted themselves respectably in a 14-3 loss to Simpson and the Trojans.

USC finished No. 1. Indiana finished No. 4. Crusan packed that 40 pounds right back on and went in the first round of the draft as an offensive tackle. It was supposed to be the start of something. The departing seniors were sure it would be, considering how many talented sophomores had two years left.

But the next two seasons in the rugged Big Ten finished 6-4 and 4-6. Pont, who passed away in 2008 at age 80, didn’t have another winning season before moving on to Northwestern. Indiana produced one first-round pick in the 17 years after Crusan went, and it’s been six total since him. Indiana is still waiting on that next Big Ten title and Rose Bowl.

“We’ve never had the resources,” said Kaczmarek, who went on to become chief financial officer at Merrill Lynch and Blue Cross California. “But we do now. And we finally have a coach who’s a total football coach.”

The 1967 Hoosiers, whose reunions continue to get smaller — Isenbarger passed away in March at age 76 — think it’s different this time. Stolberg, a developer who has endowed a football scholarship and is part of the Presidents Circle as the highest level of donor, can speak to the economics. One, things have changed a bit since he played and players did everything their coaches said and found contentment in a scholarship.

“I mean, we had a few handshakes with a little bit of money, but nothing special,” he said with a laugh, and two, he’s confident that Indiana is prepared to support Cignetti’s program at a championship level in the years to come.

White, a donor who spent many years raising funds at IU, attended Cignetti’s first practice in the spring and said it was “immediately eye-opening.” Krusan comes from Western Pennsylvania like Cignetti, loves his approach and said: “I know that coach. I’ve known that coach my whole life.”

“Do I think it can last?” Stolberg said. “I really do.”

White does, however, still remember something an Indiana classmate told him late in 1967 after passing on the trip to Pasadena: “I’ll just go next time.”

“That’s why I’ll be at Notre Dame for this one,” White said. “You never know for sure. You can’t take those chances.”

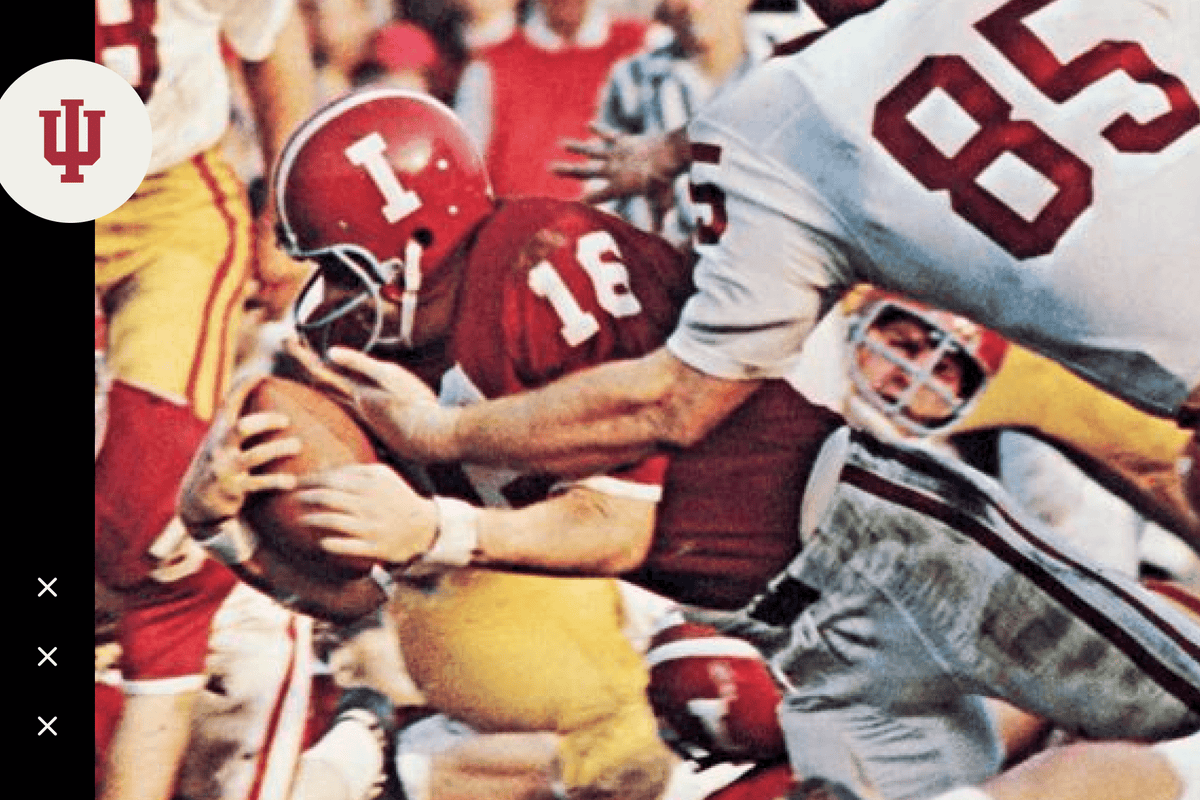

(Top photo of Harry Lee Gonso courtesy of Indiana Athletics)