Please be advised that this article contains reporting some people may find distressing.

“I loved my son very much. I can’t talk about him without crying,” says Mory Sanoh, as the tears come again and his voice breaks. “Who can bear such a tragedy?”

Lacinte, his seven-year-old son, did not make it out of the Stade du 3 Avril alive on December 1, as one of the world’s worst stadium disasters unfolded in Nzerekore, the second-largest city of the West African country Guinea.

“My son went to watch the game. When I returned home from work, everyone was asking about him. Then I heard there had been an incident at the stadium,” Sanoh tells The Athletic from his home in the south east of the country.

“I’m in a lot of pain. That a child you loved very much should be taken away from you? I leave it to God, I have no other choice, because if I did, I would make those responsible for his death pay.”

Guinea’s government says 56 people died in the disaster, but domestic human rights organisations believe they have verified that at least 135 people — a significant number of those children — have lost their lives. Investigations into what happened and why are underway as some people still search for their loved ones at hospitals and morgues.

“I saw death that day. There were many dead people around here,” says Amadou Doumbouya, sitting at his refreshment stall across the road from the community stadium. “I saw bodies that people were carrying in their arms to take them back to their families. Others were brought to the youth house on the other side. There were even bodies that were dumped in the alley on the other side. I saw it all.”

The majority of the victims died as fans ran towards the main entrance of the stadium after police and security forces fired tear gas inside the venue to combat crowd disturbances towards the end of a heated match between local side Nzerekore and Labe. The game was the final of a tournament designed for younger supporters and linked to Mamady Doumbouya, the military leader of the nation.

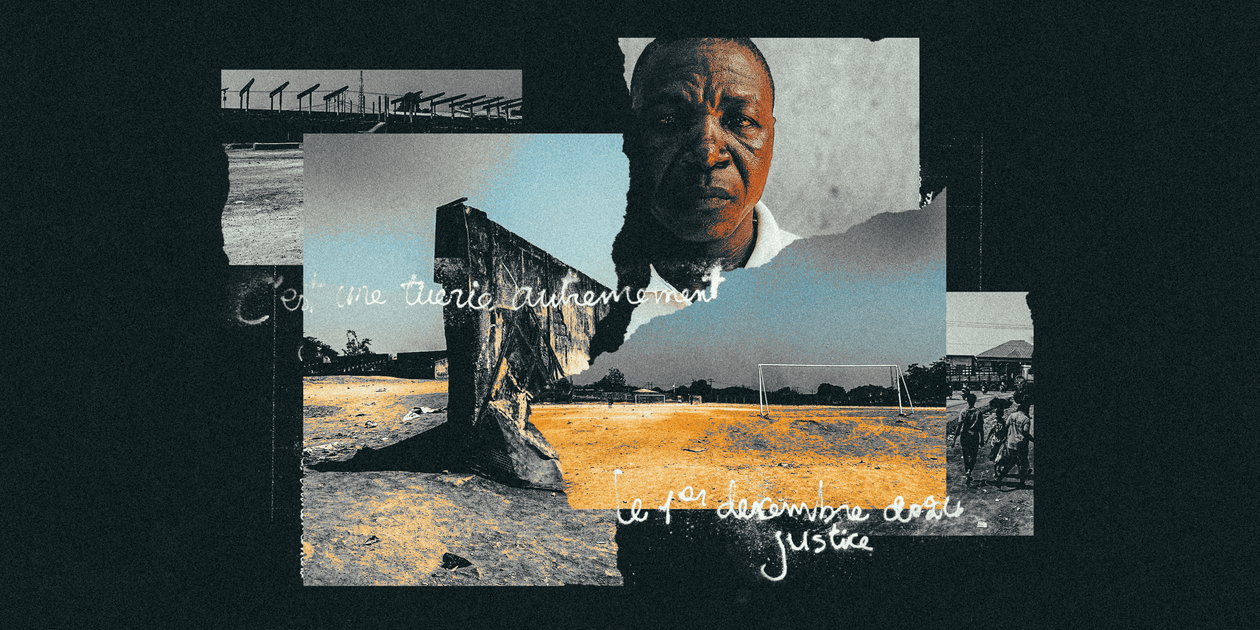

Today the ground bears the scars of its tragedy. When he thinks of the main gate, Emmanuel Sagno from the Guinea Organisation of Human Rights (OGDH), says: “This door here, it’s the door to hell.”

The Athletic travelled to Nzerekore — which has a population of approximately 200,000 — to visit the stadium, analyse what happened and speak to eyewitnesses and relatives, like Mory and many more, who are grieving and searching for the truth.

The main gate is a picture of contorted metal in Guinea’s national colours of red, yellow and green. It echoes the pain and fear of December 1.

One of its doors is precariously hanging onto the concrete wall by its lower hinge, the other forced off its fixings entirely in the most significant fatal crush at the stadium. Both doors are twisted and bent out of shape, their frames buckled as a reminder of the force that tried to make its way through in the chaos.

The perimeter wall and one of the exit gates at the stadium (Adam Leventhal/The Athletic)

Just a few hours before the game, fans excitedly flooded in off the busy road outside, many on their motorbikes that were parked on the outskirts of the Stade du 3 Avril, which commemorates the start of Lansana Conte’s presidency after a coup in 1984.

People had come for the final of a two-week tournament put on by a youth organisation — Alliance des Jeunes Leaders du le Foret (Alliance of Young Leaders of the Forest) — to garner support for Doumbouya, the military leader. The trophy bearing his name was paraded before the match.

This was the climax of the ‘Refoundation’ tournament, targeted at younger supporters. It was free to enter, meaning a ground that usually holds 5,000 swelled — according to those at the game — to closer to 15,000 or 20,000. The game was originally due to begin at 2:30pm, according to referee officials, but organisers — who wanted to ensure they got the chance to rally the crowd with political messages — pushed it back until 5pm. The consequence? More and more people came in.

Before the game, there was a colourful carnival but, by the end of the day, it was carnage.

In the 68th minute of the match, the first contentious decision drew a heated response from the crowd. “The referee gave what he thought was a second yellow card to a player from Labe, so there was a bit of noise when he gave the red card,” explains Marie Louise Caulier, a journalist based in Nzerekore. “It was corrected to just a yellow and the organisers and authorities managed to calm people down and they resumed play.”

As the game — on the uneven, sandy surface — reached its climax, tempers flared on the field. “There was the penalty disputed and I saw a stone thrown from one corner and I said, ‘This isn’t going to end well’. The size of the crowd scared me,” says Andre Sagno, a local teacher, who was also at the game.

“Suddenly everyone started running and in the chaos, we all went to one door. But then we were being suffocated by the tear gas. There were (also) stones being thrown to the east.”

The majority of the fans headed to the main gate but initially, it was not fully open and the weight of human traffic quickly led to a bottleneck. As the gates were pushed out, people at the front were crushed and fell, those behind could not move and a mass of bodies became stuck with more and more pressure coming from behind.

“We saw a route to the big gate, so we rushed out, but those ahead of us had no access to get out,” says Feromo Beavogui, another journalist who attended the match. “When those on the outside realised there was a commotion on the inside, rather than opening the gate, they continued to barricade the exit.”

Beavogui was edging closer to the main gate: “We were stuck in the middle of a huge crowd. I was in the crush, but someone saved me by grabbing my hand and pulling me up. I was lucky I had my hands up, otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to get out. Throughout this, there was the tear gas, which wouldn’t stop. It just wouldn’t stop…”

Footage taken from the stand next to the main gate shows people being pushed towards the gate by vehicles trying to force their way through the crowds. In desperation, witnesses say some people ran over the top of the people who were stuck.

There were two other exits at the ground. One is approximately 100 metres along the perimeter wall in the corner of the ground. That gate was also partially blocked. One of the two doors remained closed, meaning a six-metre opening — similar to the main gate — was only three metres wide. People died at that gate, too.

At the opposite end of the ground, there was a third exit, which was only marginally wider than a normal household door. In the panic, people broke through the concrete wall next to it to try to make their way to safety as another crush developed.

“We rushed to the smaller door, but there we were threatened,” says teacher Sagno. “Some hooligans were mixed up with the security, they were pickpocketing, I even saw knives being used to threaten some people. So we had little choice but to climb the wall to get out. You would climb the wall and then help someone else up. We barely saved our lives. The images of that day still haunt me.”

Marie, who had recently given birth via caesarian section, was nearby.

“We tried to leave on the other side through the small gate,” she says. “But they (security forces) threw more gas in front of us. So we turned around. I took my vest and put it up to my nostrils, but it wasn’t helping. My eyes, my nostrils, everything hurt. I couldn’t breathe. My friend said, ‘We’ll jump the wall’. I said, ‘I can’t jump the wall, If I try to go over there I’ll die’. Besides, can I climb the wall in my condition?”

The walls are approximately 10 feet tall (three metres) on the inside of the ground, with the road level lower down outside the perimeter, meaning the drop is significantly greater in some places. Some were severely injured or died as they fell.

“We didn’t know where to go and we were running around breathlessly. Fortunately, there was a regional inspector who I’d like to thank. He’s the one who helped us. We got into his vehicle and stayed there until it was safe.”

Many didn’t find sanctuary or any way out.

As the light dwindled on the evening of December 1, bodies lay on the ground outside the stadium and on the pitch. Cars ferried the dead and dying to the hospital, which quickly became overwhelmed. Bodies were lined up in the corridors.

Some families took their relatives home with them without any record of their death or post-mortem carried out, making a comprehensive final death toll difficult to establish.

Amid the chaos, anger was directed at those in charge at the ground. The local police station just a few hundred metres away was set alight and vehicles belonging to the organisers were also burned. The charred shells of the vehicles remain two weeks on, the station no longer in use.

The burnt-out police station in Nzerekore (Adam Leventhal/The Athletic)

The police and hospitals in the area declined to comment to The Athletic. The organisers (the Alliance of Young Forest Leaders) issued a statement in the hours that followed, but have also not responded to requests for guidance.

The statement read: “Following the tragedy that occurred at the stadium on April 3 during the final of the re-founding tournament held from November 16 to December 1 in Nzerekore, the Alliance of Young Forest Leaders, in the voice of its president, expresses its sincere condolences to the parents of the victims and salutes the promptness of the republican government in taking care of the injured and managing the bodies and other collateral damage.

“This sports competition, which was intended to be a moment to strengthen the social fabric and live together, has unfortunately turned into a drama, causing the loss of human lives and several serious injuries.

“As the main organiser of this tournament, we wish a speedy recovery to the injured and eternal rest to the dead.”

The police and security forces are blamed by many of those at the game for firing the tear gas rounds that created a dense noxious fog in the stands and pitch area. The Athletic contacted the government to ask whether they regarded this action as proportionate in the circumstances but received no response at the time of publication.

Prime Minister Amadou Oury Bah made a flying visit in the hours that followed the disaster, but it only lasted a few hours before he returned to the capital, Conakry, 500 miles away. Three days of mourning were announced and Bah Oury, as he is commonly known in Guinea, ordered the courts to open an investigation into the events in Nzerekore.

In a statement after the tragedy, the government said: “The High Authority for Communication (HAC) learned with deep sadness of the unfortunate outcome of the final of the football tournament on Sunday, December 1, 2024, in Nzerekore. It presents its condolences to the grieving families and wishes a speedy recovery to the injured in these difficult times.

“Given the social impact of this circumstance, the HAC asks journalists for more professionalism and responsibility in dealing with this painful event that afflicts the entire Guinean nation.”

FIFA’s stadium safety and security regulations expressly say that “no firearms or crowd control gas shall be carried or used” in stadiums.

“I call on the relevant authorities to ensure that the appropriate steps are taken to ensure similar incidents do not occur again and that all players, staff, officials and supporters are safe to play, watch and enjoy football anywhere in the world,” said FIFA president Gianni Infantino.

Football’s world governing body has advised The Athletic that it will allow the Confederation of African Football (CAF) and Guinea’s football federation (Feguifoot) to take the lead on the matter. Feguifoot is taking international and continental club fixtures outside the country due to political instability.

All three football bodies advised The Athletic that the match at the Nzerekore stadium was deemed an “unofficial” game and therefore they are not obliged to look into it. “We give space to government in the country to conduct necessary investigations,” a CAF spokesperson told The Athletic.

Inside the Stade du 3 Avril (Adam Leventhal/The Athletic)

Whether unofficial or not, Nzerekore has followed in the footsteps of two other significant tear gas-related football incidents in recent years. In 2022, Liverpool fans were penned in outside the Stade de France in Paris before the Champions League final. Later that year, at least 135 people died at the Kanjuruhan Stadium in Malang, Indonesia, after police fired tear gas into the stands, leading to crushes at multiple gates.

GO DEEPER

At least 135 dead, 51 of them children – a year on from the Kanjuruhan stadium disaster, what has been done?

People want answers.

Mamadi Sanoh lost his 10-year-old son in the Nzerekore disaster. “These announcements are meaningless,” he says. “Because since the tragedy happened, we have not seen anyone from the state come to console us and ask how we feel to show that they are with us. They just came to write our names and the names of our missing sons on lists, that’s all.”

Some have still not found loved ones two weeks on.

“The children went to the stadium without me knowing,” explains Amara Soumaoro, sitting outside his home. “When they heard the final was at the stadium, they hid to get there. When the chaos started, it was my wife who called to inform me that the children hadn’t returned home yet.

Amara Soumaoro eventually found his daughter but has not been able to locate his niece (Adam Leventhal/The Athletic)

“I searched for them all night but couldn’t find them. It wasn’t until the next day, around 10am, that I found my little girl (Matenin, 10), who was badly wounded. She had fallen into the pushing crowd and people stepped on her. She had several wounds on her head and face. Her condition was very critical.”

His niece, Mafatta Sagno, 16, is still missing: “We have no news of her. We don’t know if she’s alive or dead. We’ve done everything we can to find her: broadcast messages on the radio, went to the hospital, the military camp and alerted the security services, but nothing. If I’d at least seen her body, there’d be an answer. We have no trace of her. Where is she? That’s what we want to know.”

Mory Cisse recently lost his elderly father, Mamadou. His younger brother, Lansana, had come from out of town to Nzerekore for the funeral. He stayed an extra day for the game and the brothers went together. Maurice left early to go to his niece’s wedding — it was the last time he saw his brother alive.

“I couldn’t get through (when I learned of the incident). I did everything I could, it rang, but nobody picked up, so I was really worried,” he says.

“I went to the hospital and saw a lot of dead people there. I started looking for my younger brother among the corpses, but I couldn’t find him. Then I looked at the mortuary. I looked and looked and then yes, I found him. It’s unbearable.”

Joel Gbamou searched for 24 hours for his nephews, Delphin (18) and Dominique (13), whom he called his sons. “Eventually someone in the morgue said he had seen the bodies, so I had to go in and identify them,” he says. “It’s been a huge shock. I am trying to be strong. If you met my family, then you would see how emotional they are.

Joel Gbamou lost his two nephews in the tragedy (Adam Leventhal/The Athletic)

Emmanuel Sagno is in charge of the region’s non-governmental human rights defence collective, the OGDH. It has worked to clarify the real death toll of the tragedy by visiting hospitals, morgues, mosques, churches, schools and places of work.

“Three days after the incident, we declared at least 135 were dead, having spoken to multiple different sources. But that number may be much higher,” he says. “One father told us that all five of his children died in this tragedy. He is inconsolable.”

He says the factors that led to the disaster include overcrowding and “the excessive use of tear gas”. He says the government should work collaboratively with the human rights organisations.

“If they want to get to the truth, it should be done together. In the meantime, our goal is to identify the victims and provide them with all the psychosocial support they need to overcome the situation they’ve lived through,” he says. “We want to make sure there is enough humanitarian support, whether that’s food or friendship. We need to lodge complaints with the national and international courts so justice can be met.”

Emmanuel Sagno is the head of the local human rights collective (Adam Leventhal/The Athletic)

On Friday, Amnesty International called for an “independent and impartial investigation” into what went on at the stadium and the behaviour of the security forces.

“The government’s current silence, coupled with a restriction on internet access in the city, rightly raises suspicions about the authorities’ willingness to take the full measure of the tragedy,” said Samira Daoud, Amnesty International’s regional director for west and central Africa.

“Based on credible information, many organisations and witnesses interviewed by Amnesty International have denounced the inaccuracy of the official death toll following the incident at the stadium, arguing that it could be much higher.”

The United Nations called an emergency meeting to coordinate an immediate response to help with humanitarian, medical and psychological assistance for victims and their relatives. The organisation’s Guinea coordinator, Kristele Younes, said: “This tragedy is a painful reminder of the crucial importance of ensuring safety in public places. The authorities’ commitment to conduct a thorough investigation is an essential step in shedding light on the facts, strengthening preventive measures and ensuring justice.”

The aid organisation already works closely with UNICEF, the World Food Programme and the World Health Organisation in the city, with regular humanitarian aid flights to Nzerekore.

At the stadium, graffiti on the walls demands justice. The children who escaped the tragedy have started to return and they play football on the patch of land next to the main gate where so many young lives were lost.

One boy makes a line in the sand to mark out the pitch. Life goes on in Nzerekore, but the search for the truth — and justice for the dead and missing — has only just started.

(Top photos: Adam Leventhal/The Athletic; design: Eamonn Dalton)